Startup integrates public databases and georeferenced data into rural land analyses for ESG targets

Through its participation in the Sustainable Soy for the Cerrado Program, Busca Terra has incorporated socio-environmental analyses and rural land-holding surveys into the portfolio of services for traders and farmers.

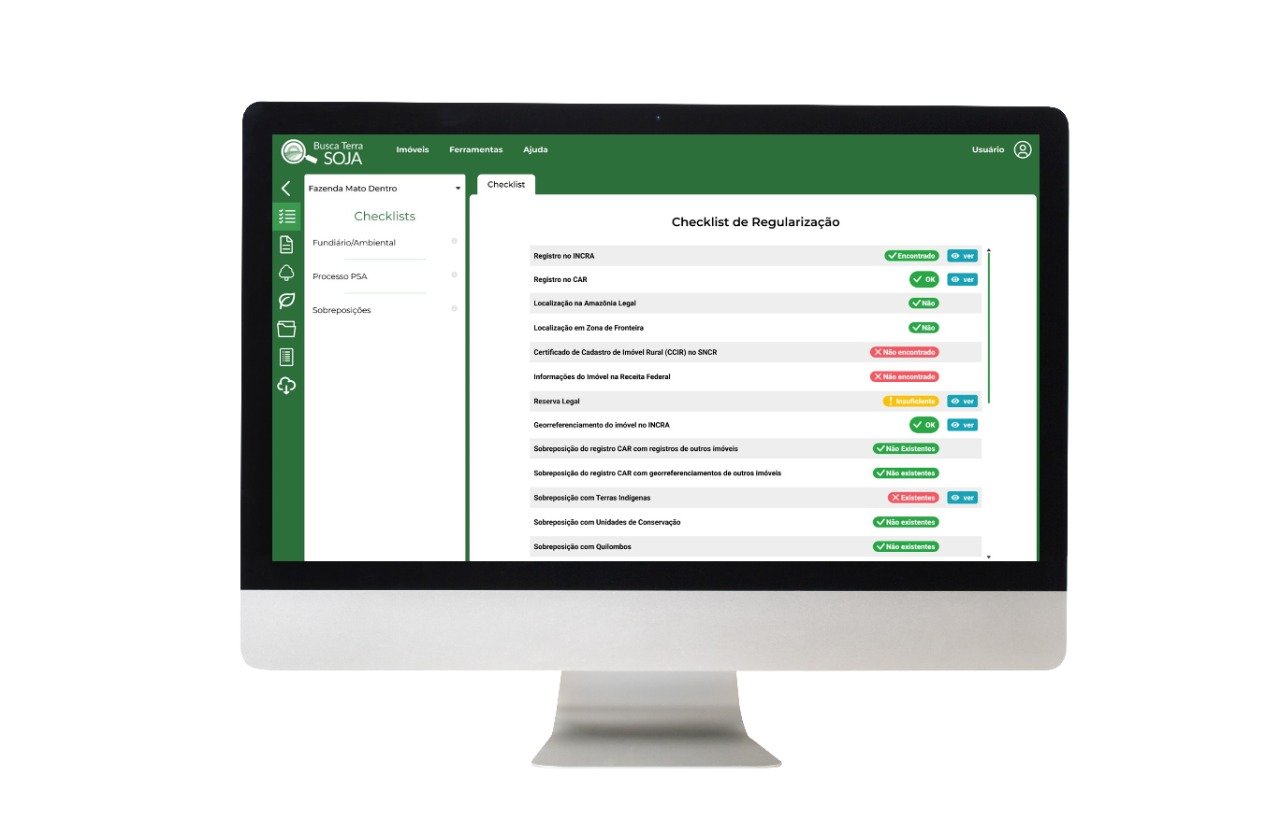

A monitoring and traceability platform for companies to prove they are buying soy grown on farms that comply with landholding and socio-environmental laws is the innovative solution being developed by Busca Terra, a startup selected by the Sustainable Soy in the Cerrado Program for financial support from the Startup Finance Facility. With the Soy Transparency Platform, which has just hit the market, the startup's aim is to offer a single, spatialized, and georeferenced database, using a broad range of data to feed a positive registry of soy growers. The registry aims to stimulate green business opportunities for farmers in compliance with the federal Forest Code, by offering a "Green Soy Seal."

Busca Terra gathers data on rural land from more than 100 different databases – INCRA, the Rural Environmental Registry, the Federal Revenue Service, IBGE, IBAMA and the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAPA), to name a few – combining information on climate, soil, landholding and registration variables, deforestation alerts and fire outbreaks. The monitoring includes assessments of governance (ownership, overlap with public areas and other rural holdings, proper titles, certificates, and registrations), social requirements (labor analogous to slavery, overlap with quilombo and indigenous areas) and environmental concerns (sufficient legal reserves and permanent preservation areas, fines, certificates, etc.).

Far beyond the CAR:

What sets the Soy Transparency Platform apart is how it integrates socio-environmental and land-holding criteria into data analyses for the market. By combining public databases, satellite information and artificial intelligence (AI) analysis, the startup offers an agile, transparent service whose analysis goes far beyond that of the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR), to achieve ESG targets which companies and institutions must meet. "If your socio-environmental analysis is based solely on the CAR, you're shooting yourself in the foot," says Rafael Fonseca, one of the startup's founding partners.

For Busca Terra's partners, the CAR is not a good tool for land-holding and environmental analysis. Based on a declaration with information provided by the farmer alone, it leaves inconsistencies in the database that jeopardize any appraisal of a farm's precise perimeter. "The Rural Environmental Registry was created to determine whether farms have legal reserves or permanent protection areas, i.e., to see if there is still any native vegetation in the area. It is environmental, not land-based. We created our system to offer a more rigorous service to companies and farms, and to add value for compliant farmers," adds Rafael.

Farmers who sign up with the startup will receive reports with qualitative, tailor-made analyses of their farm and suggestions on how to overcome any irregularities. Farms meeting all the legal requirements receive a Green Soy Seal (“Selo Soja Verde”) and are listed in the startup's public pool of suppliers. Only farms that meet 100% of a list of minimum conditions will be listed on the Soy Transparency Platform. For any outstanding issues, owners can either request technical support from the startup itself to become compliant or outsource the service to a third party.

Busca Terra's goal is to enable farmers in good standing with their socio-environmental registries who adopt best agricultural practices to gain access to payments for environmental services, preferential prices for their produce or special agricultural credit opportunities, for example. "We want partner companies to offer financial benefits to farmers accredited with the Green Soy Seal," says Rafael.

From land-holding analyses to socio-environmental assessments

Busca Terra was founded in 2019 to meet the demand for quick, well-structured access to consolidated data on farms. Biologists by training, specialized in geoprocessing and computing and with backgrounds in providing services to public agencies, the partners decided to create a platform that could gather disparate data from various databases into a single platform for quick, reliable analyses of a farm's legal and socio-environmental status. "It's hard for farmers to know what they need to do. Most of them want to get it right, but they don't know how".

For almost a year, the partners managed more than 70 WhatsApp groups with around 5,000 members and a Facebook group with more than 70,000 users, all focused on farm properties. "We use this direct dialogue to get to know farmers' needs and chart their demands," explains Rafael, a farmer himself and very familiar with how hard it is to access clear, consolidated information about one's farm.

The partners say the challenge of legalizing ownership of rural land can involve exhaustive searches for family records and land deeds lasting decades. "It's often so complex that institutions can't help the person. It means investigating generations of a family," explains Sérgio. In one case, they had to go back over 100 years to discover the origin of a piece of land purchased about a decade ago, in the interior of São Paulo, with problems in its CAR. "We went back as far as the time of Dom Pedro II, who gave the land to a former slave. We went through the whole chain until we found where the land grabbing took place. Someone bought 50 hectares, added another zero and it became 500. Since then, the farm has four deeds for the same property that doesn't exist in the real world. This is in São Paulo, where land regularization is very advanced. Imagine what goes on in the Amazon," he adds.

Often farmers don't know they have a legal problem to solve until their CAR is rejected. Another common situation experienced by farmers is hiring a company to file their CAR and then not being able to find it again, and not knowing how to use the system to update data. There are also mistakes in the registry, such as overlapping areas or insufficient legal reserves. Finally, there are records that point to areas with no vegetation. "They write a perimeter into the system, but in practice it has a swimming pool, pasture, housing. The system only considers the area mapped in the filing," explains Sérgio.

The partners believe that there is a real need in the market for analyses combining land and socio-environmental data, especially for small and medium-sized farmers. Participation in the Sustainable Soy for the Cerrado Program was the path they chose to add socio-environmental conditions to the startup's land and land-title analysis, broadening its range of services for companies and farms. Currently, the startup has data on soy crops in South America for the past decade, with geographic breakdowns and percentages of conversion of native vegetation by area.

“The Rural Environmental Registry was created to determine whether farms have legal reserves or permanent protection areas, i.e., to see if there is still any native vegetation in the area. It is environmental, not land-based. We created our system to offer a more rigorous service to companies and farms, and to add value for compliant farmers," adds Rafael.

Since then, Busca Terra has incorporated deforestation and land cover indicators into each farm's monitoring and traceability requirements. Funding from the Startup Finance Facility made it possible to produce the Soy Transparency Dashboard and implement the Green Soy Seal. The startup’s package to help farmers with environmental compliance includes mapping the property using an app, uploading offline photos, images, and videos, automatically integrating georeferenced data into the Busca Terra platform, simulating environmental services payments to compliant farmers, delivering a complete report and conducting a thorough assessment of the farm’s situation.

“Entendemos que para inovar é preciso criar condições para o desenvolvimento de uma paisagem de inovação, com espaço para o intercâmbio entre os diversos atores da cadeia da soja e o fomento de soluções com potencial transformador para a cadeia da soja, em diferentes estágios de desenvolvimento”, diz Carlos E. Quintela, diretor do Land Innovation Fund. “Valorizamos a importância de soluções como a da Busca Terra, capazes de conjugar transparência, eficiência e agilidade no monitoramento de dados em favor de uma agricultura sustentável e livre de desmatamento”, completa.